- Home

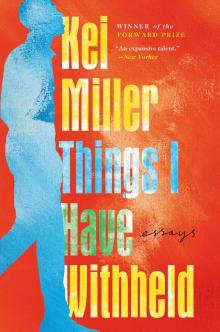

- Kei Miller

Things I Have Withheld

Things I Have Withheld Read online

Also by Kei Miller

Fiction

Fear of Stones and Other Stories

The Same Earth

The Last Warner Woman

Augustown

Poetry

Kingdom of Empty Bellies

There Is an Anger that Moves

New Caribbean Poetry: An Anthology (ed.)

A Light Song of Light

The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion

In Nearby Bushes

Essays

Writing Down the Vision: Essays & Prophecies

Grove Press

New York

Copyright © 2021 by Kei Miller

Jacket design: gray318

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer,who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copy righted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York,NY 10011 or [email protected].

The following essays have been previously published in slightly altered form: An early version of “Letters to James Baldwin” was originally commissioned by Manchester Literature Festival and published in the Manchester Review. “The Buck, the Bacchanal, and Again, the Body” and “The White Women and the Language of Bees” previously appeared in PREE. “Mr Brown, Mrs White, and Ms Black” previously appeared in Granta.

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Canongate Books Ltd

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

First Grove Atlantic hardcover edition: September 2021

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title.

ISBN 978-0-8021-5895-6

eISBN 978-0-8021-5896-3

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

For Karen Lloyd and Jaevion Nelson

who not only say, but also do, the most important things.

With all my admiration.

Forty years ago when I was born, the question of having to deal with what is unspoken by the subjugated, what is never said to the master . . . was a very remote possibility; it was in no one’s mind.

—James Baldwin, speaking at Cambridge University, 1965

CONTENTS

Considering the Silence (An Author’s Note)

1. Letters to James Baldwin

2. Mr Brown, Mrs White and Ms Black

3. The Old Black Woman Who Sat in the Corner

4. The Crimes That Haunt the Body

5. An Absence of Poets and Poodles

6. The Boys at the Harbour

7. The Buck, the Bacchanal, and Again, the Body

8. Our Worst Behaviour

9. There Are Truths Hidden in Our Bodies

10. The White Women and the Language of Bees

11. Dear Binyavanga, I Am Not Writing About Africa

12. Sometimes, the Only Way Down a Mountain is by Prayer

13. My Brother, My Brother

14. And This Is How We Die

Big Up

CONSIDERING THE SILENCE (AN AUTHOR’S NOTE)

Consider, for a moment,

the silence—

this terrible white

space;

all the things

we never say,

and why?

This is what comes to mind when I consider the silence: how I saved my words for the stairwell in Streatham Hill, London, right outside the flat where I lived at the time; how I would sit there many nights, a little shell-shocked, and mumbling to myself.

If that sounds a bit like madness, maybe it is because that is what it was. I had ended up in a bad relationship. It was never violent but always volatile. I could never predict what would set things off—what might produce the latest bout of rage. I felt ashamed as well, to be a man such as I was, such as I am—tall and black—and so fearful of a person I was supposed to feel safe with; afraid of doing the wrong thing, and especially afraid of saying the wrong thing. Instead, I saved my words for the stairwell—rehashing arguments to myself, trying to unravel them, to understand them, and wondering how I might say things better the next time.

I was often accused of being silent, which was fair. My silence was also a strategy—a way to survive. Whenever I risked words—however carefully, however softly, even if it was just to answer the innocuous question, “How are you feeling?”—it could be met with such an explosive tantrum that I quickly learned to rarely take the risk. The specifics of that experience were new to me; I had never been in a relationship like it before. My reaction, however—the way I responded—was familiar. It was an old habit. Sitting on that stairwell at nights only emphasised what had always been true for me—that the moments when I am most in need of words are exactly the moments when I lose faith in them, and when I fall back into silence.

I suspect it is the same for a great many of us. We keep things to ourselves. We withhold them because of fear—because those things that we need to say, or acknowledge, or confess, or our own failings that we need to own up to—they can feel so important, it is hard to trust them to something so unsafe as words.

The essays that follow are not about the awful relationship, but they are about things I have withheld. The book’s title is one that I have borrowed from the poet, Dionne Brand—something she once said at the beginning of one of her own essays, and which I find myself pondering over and over, the way she connects her own body to the bodies of others and the silence between:

Some part of this text we are about to make is already written . . . for that I am a black woman speaking to a largely white audience is a major construction of the text. Blackness and Whiteness structure and mediate our interchanges—verbal, physical, sensual, political—they mediate them so that there are some things that I will say to you and some things that I won’t. And quite possibly the most important things will be the ones that I withhold.

Each of these essays is an act of faith, an attempt to put my trust in words again. They are attempts to offer, at long last, a clearer vocabulary to the things I only ever mumbled, at night, sitting there on an outside stairwell in Streatham Hill, London.

1

LETTERS TO JAMES BALDWIN

Dear James,

I wish I could call you Jimmy, the way that woman you described as handsome and so very clever—Toni Morrison—always called you Jimmy, which meant that she loved you, and you her, and that in the never-ending Christmas of your meetings (this is how she described it) you sat, both of you, in the same room, the ceiling tall enough to contain your great minds, drinking wine or bourbon and talking easily about this world. I wish that I could sit with you now and talk that easy talk about difficult things—the kind of talk that includes our shoulders, and our hands on each other’s shoulders, the way we touch each other, unconsciously, as if to remind ourselves of our bodies and that we exist

in this world. But here is the rub, this awful fact—that you do not exist in this world, not any more—at least, not your body; only your body of work, and I can only write back to that and to the name that attached itself to those words rather than the name that attached itself to your familiar body. Not Jimmy then, but James—a single syllable that conjures up kings and Bibles—appropriate in its own way, except it does not conjure your shoulders or your hands which I imagine as warm and which I never knew but somehow miss, and I am writing to you now with the hope that you might help me.

Dear James,

I read your review of Langston Hughes. “Every time I read [him],” you wrote, “I am amazed all over again by his genuine gifts—and depressed that he has done so little with them.” “The poetic trick,” you went on to say, moving from review to sermon (because there was never a pulpit you could refuse, and never a pulpit you did not earn), “is to be within the experience and outside it at the same time.” You thought Hughes failed because he could only ever hold the experience outside, and you understood the why of this—the experiences that we must hold outside ourselves if we are ever to write them and not be broken by them.

But you were never able to do that. You were never able to write anything that did not implicate your own body.

James, here is a truth: I do not think much of your poems, and I suspect you will not think that a cruel way to start this exchange, and that it says more about me and my insecurities that I must begin in this way of making you fallible, approachable. To read you as I have been reading you all these years is, quite frankly, to encounter majesty—something enthroned, something that can only be approached on one’s knees, with one’s eyes trained to the floor. I know that image would bring you no comfort or pride, to have a black man so stooped, so lowered before you. Forgive me then my truth. I read Jimmy’s Blues and was struck by your genuine gifts and how little you had made of them.

That isn’t really fair. I know. You had never tried seriously to be a poet. Jimmy’s Blues was more our collection than it was yours—just our own desperate attempt to read something new from you, to find once again in your words some shard of beauty and truth. So we gathered together the few poems you had written—one here, one there—and put them together in a book you had never imagined. And the thing is this: the beauty was there, the elegance of thought we have come to expect from you—but the beauty was cumulative, a result of the whole poem and not of its individual parts. You were always poetic but you weren’t quite a poet—though you could have been. You could have been amazing. You didn’t know how to pack enough into that most basic unit of poetry—the line.

What Hughes had, and what I think you lacked, James, was an instinctive understanding of the form of poetry, of the lyric line and what could be contained in it, and how that line might break and how it might take its breath. But I think if you and Langston Hughes were one person, James Hughes maybe, or Langston Baldwin, if such a person had written poetry—poems in which the body was present and vulnerable, and that broke in the same soft places where lines break—I think I would not have survived. I think I would have read such poetry and not been able to breathe.

Dear James,

I think about why we write letters—as an antidote to distance, as a cure for miles and the spaces that stretch between us. If the beloved were present, there would be no need to write. I think about the distance that is between us, which is only the distance of life and death and nothing more, because (and this is painful to say) there is little between the world you described, the set of circumstances you wrote of, and the set of circumstances we live in now. And what I want from you is a way—a way to write the things I have been trying so hard to write.

James, I do not think much of your poetry, but I think everything of your essays and it is essays that I have been trying to write but have stopped and need your help. What you had and what I lack is an instinctive understanding of the form—the sentence that you could make as clear as glass, style whose purpose was only ever to show and never to obscure—and how you could write these things that were so muscular and so full of grace is a wonder to me.

The essays I’ve been writing—they began because of something Dionne Brand once wrote about “the most important things”. She suggested the most important things are, in fact, the things we almost never say, because of fear, or because we think they can only be said at the cost of friendships. I have been wondering how to say them.

“We still live, alas, in a society mainly divided into black and white. Black people still do not, by and large, tell white people the truth and white people still do not want to hear the truth.” Oh James . . . ain’t that the goddamn truth!

James, there are still men who wear white sheets in that country to which you were born, and who burn crosses and who march in support of the Aryan nation. There are still men who tattoo Nazi signs onto their skulls, and people who spit at me and call me nigger. I have no desire to write to such people, to condemn them, because that kind of racism, that kind of hatred is so unimaginative, so obviously deprived of reason and morality that why I should waste words or intellect on it is strange to me.

But the big, terrible things distract us from the other things, which are both smaller and more urgent, and prevent us from loving or trusting each other. I think about why I write essays—as an antidote to distance, as a cure to what stretches between my best self and my worst self, or between my friends, however close we are—the people I laugh with, the aunts who I kiss, the men I have kissed, the people I love, the people who want to be good people, who try every day to be good people, to do good things, but how so often between us, between our love is this black and white world, these truths that, by and large, I do not say and by God, we do not want to hear.

Dear James,

It is the body that I wish to write about—these soft houses in which we live and in which we move and from which we can never migrate, except by dying. I want to write about our bodies, and what they mean, and how they mean, and how those meanings shift even as our bodies move throughout the world, throughout time and space.

I do not often like to think about my own body, or even look at it. Left to itself, my body relishes in fatness and a general lack of definition, though this is not true at the present moment. At the present moment my body is hard and muscled because I have been swimming and going to the gym and running and trying hard to undo the things that my body would rather do. I look in the mirror now and wonder how long this new shape will last. I do not like to talk about my body, because I might have to talk about its weight, or else the weight of my insecurities. But I must talk about it, because it has meant so many things in so many places.

At an immigration desk in Iraq, before boarding the plane that will take me away, I am pointed towards a small room. I cannot remember much about that room now—if there were windows or if there was a ceiling fan, its slow blades uselessly stirring the warm air. This is what comes to my mind now—a windowless room and a useless ceiling fan, though I am not confident in the memory. In the small room I am ordered to take off all my clothes. I fear that they will put on latex gloves, that they will put a finger inside my body searching for drugs. They will not find any. I wonder when it was that Iraq became a popular departure point for drug mules, but I do not wonder what it is about my body that has aroused suspicion. I am used to it. I am used to being pointed to small rooms. I am used to being interrogated again, and again, and again. But I’ve never been asked to strip before. I stand there with my trousers and my underwear pooled around my ankles. I am aware of the pudginess of my belly, aware of my penis, unimpressive in its flaccidity, aware of a bead of sweat that has escaped the pit of my arm and is now running down my side. They sit—three men in uniform—and silently observe my body, and suddenly this does not surprise me either.

All week in Erbil, I had been literally chased by men as I walked along the streets. It had scared me at fir

st—seeing them lift up their thawbs like modest British women from the nineteenth century and run towards me. What seemed threatening at first was usually defused when they handed me their phones and through a series of gestures, a sort of sign language, made me know that they only wanted a picture. A picture with me and my strange body. So here, in this small room, it does not surprise me that these officials who have the power to stop me, who have the power to order me into a small room, who have the power to order me to take off all my clothes, have done that. They have ordered me to strip and they do nothing more than observe my body for a minute or two and then they tell me to put my clothes back on and leave.

I am always being stopped. In New Zealand, in Dubai, in France, in Miami, I am stopped. The officers have looked carefully from my passport and then to my face, and all the time assessing me, sizing me up, and my body—this body that must be spoken about—this body that in some contexts arouses suspicion, and in other contexts, lust, in others anger, in others curiosity—this body that has meant such different things to such different people—I must talk about it, and about its meanings.

James, I must talk about my body as black, and my body as male, and my body as queer. I must talk about how our bodies can variously assume privilege or victimhood from their conflicting identities. I do not want to talk about racists or classists or sexists because most people in the world do not assume themselves to be these things. I do not assume them about myself. And yet I know we participate in them all the same—in racism and classism and sexism. We participate with the help of our bodies, or because of our bodies—because our bodies have meanings we do not always consider.

Dear James,

I am writing this letter from an airport in Florida, an airport named after the city which it serves, but which you must not confuse for that city. Airports seem to be their own places and never really a part of the cities that claim them. There is such a keen sense, as there is in hospitals—of formality, sterility and limbo—of not being in a place but being between places, of being in a space between the life where you were and the life that you are heading to. I am always in airports, in this strange collection of wings and tarmac and glass doors and duty-free shops.

Things I Have Withheld

Things I Have Withheld